‘The Girl on The Train,’ Film Quality and Cinemetography

November 3, 2016

The 2015 novel “The Girl on The Train” by Paula Hawkins, a book filled with “unreliable narration, suspicious characters and ugly emotions,” (according to The New York Times) inspired a movie released on October 7 that earned $24 million opening weekend.

As I wrote in my review of the book on Oct. 27, “[The novel] follows Rachel Watson, a woman who has struggled with severe alcoholism ever since she discovered her husband of five years was involved with another woman. The story begins two years later and revolves around Rachel’s obsession with a couple (Maggie and Scott) she sees from her train window each day during her commute… When Maggie goes missing, Rachel pulls herself into the investigation, believing she has information the police do not.”

Though Rotten Tomatoes gave the movie a 44 percent critic rating, I found the movie incredibly enjoyable. Director Tate Taylor—also known for his work directing “The Help” and “Winter’s Bone”—did an excellent job fitting the 300-page psychological thriller into a 112-minute movie.

I was most worried about how the flashbacks would be portrayed in the movie; I often find backstories lacking in book-to-movie adaptations. “The Girl on The Train” depicted the flashbacks well, using only a simple black screen and explanation to show the history of characters.

As a whole, the movie did a good job following the steady reveal of information as the novel does.

Of course, the plot was not followed exactly (as in all book-to-movie adaptations) and drama was added through actions only alluded to in the book, the actors and actresses portrayed their characters excellently.

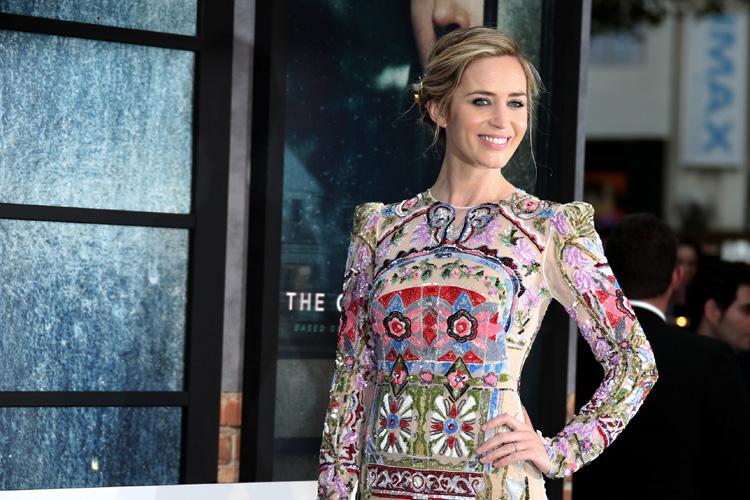

Golden Globe winner Emily Blunt, Haley Bennett and Golden Globe nominee Rebecca Ferguson starred in the film.

Blunt’s acting gave me a visual the book had been incapable of providing. Her acting was so enthralling, I had to stop myself from feeling sorry for the sobbing, alcoholic mess her character was. The other actors weren’t nearly as convincing as Blunt; their emotions didn’t seem as raw and tangible as Blunt’s. This less-than-superb acting lead to a climax that wasn’t as exciting as that in the book.

However, the quality of the film itself made me appreciate the movie more. The cinematography portrayed the theme of the movie well. I appreciated the subtle fact that the camera work was shaky only when it focused on Blunt’s character—Rachel—when she was inebriated. The sets chosen included houses with just enough charm to appear unsettling through misty weather. The music didn’t compete for the audience’s attention, but supported the themes in the film.

Additionally, the movie used much stronger language than the book did. This did an incredible job increasing the emotion movie-goers were meant to experience. Even I—the prude—wasn’t disturbed by the intensity of the f-word being thrown out every 20 minutes.

Though some critics (such as Brian Lowry from CNN) believe “the flashback structure isn’t wholly satisfying and the climax leaves and abundance of questions,” I found the movie riveting from beginning to end.

Many movie adaptations struggle to portray the eloquence of a novel, but Emily Blunt’s expert acting and the high quality of cinematography made me thoroughly enjoy the film.